Locally-Led Regenerative Agriculture Cultivates Resilience in Rural Kenya

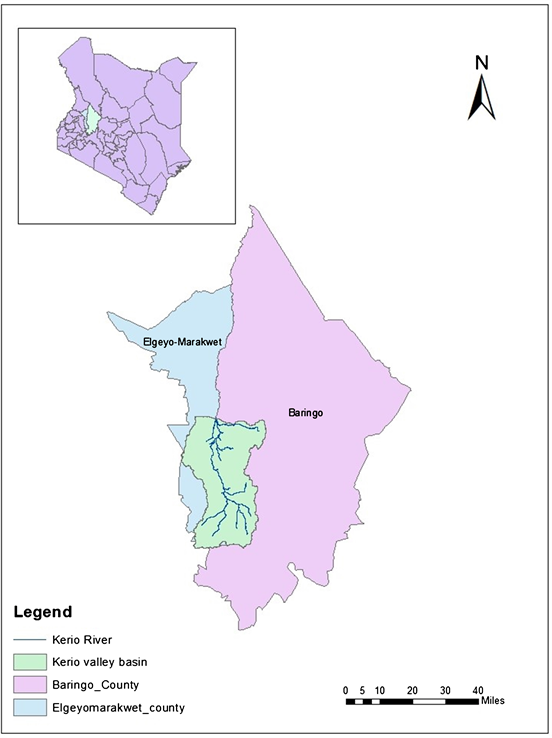

Communities living in Kerio Valley, in the lower-lands of Baringo and Elgeyo Marakwet County (EMC), are pastoralists. It is odd to drive a few meters down the road, without encountering unmanned herd of sheep and goats grazing by the roadsides and cattle lying under the Accacia trees, chewing cud. If you listen quietly, the melody of birds chipping, crickets chirping, roosters crowing and cow-bells jingles will let you know, you are not in the city anymore — welcome to rural land.

Kerio valley experiences erratic weather patterns. The community grapples with adverse effect of soil erosion, causing mudslides, landslides and Flooding, that has claimed lives of people and livestock.

According to John Korir, the County Commissioner of Elgeyo Marakwet —majority of problems experienced in the lower lands are as a result of human activities taking place in the hanging valley (plateau).

“The exploited community forest found in the plateau, is what is causing a lot of challenges in the region. Because of pressure for land, people are opening up more agricultural area, by clearing trees in their communal land and in the process, destroy fragile ecosystem.” Korir says. “This are areas with gradient (steep slope) of over 70%, and certain farming practices cannot be conducive — When you have the elements of weather mixing with unsustainable human action, it makes us more vulnerable to the impacts of soil erosion.”

“The loss of vegetative cover, causes plenty of surface run-off, which washes over the escarpments, making it susceptible to Rock falls and Mudslides.” says Simon Cheptot, the County Director of Meteorology Department. “When this water gets down to Kerio valley, it causes gully erosion and flooding.” Adding that Kerio Valley is classified as a Climate sensitive region — An Arid and Semi-Arid area (ASAL) .

“The water in Kerio valley comes from the highlands. This water has been fluctuating a lot due to climate change, making it difficult for the community to sustain their livelihood.” Cheptot says. “The rainfall pattern in the lower-lands has become unpredictable and the temperature can get to 33 degrees Celsius. These changes in the atmospheric condition, has facilitated the rise of invasive species.”

According to the United Nation’s Convention on Biological Diversity, ‘Invasive alien species are species whose introduction, threatens biological diversity — For a species to become invasive, it must successfully out-compete native organisms, spread through its new environment, increase in population density and harm ecosystems in its introduced range.’

Assessment of Soil Erosion and Climate Variability on Kerio Valley Basin by Jomo Kenyatta University — concluded that climate change was a major factor in the changes happening in the basin.

To be sure, human factors play a role too, but the study calls for increased conservation efforts in the ‘wake of increasingly climate variation, in order to establish ecological balance and protection of increasing reduction of species that were once common in the area.’

In the face of so much disheartening news, the story of Samuel Teimuge and Konyasoi vetiver network, is a reassurance that by adapting to Climate change, a vulnerable community can thrive.

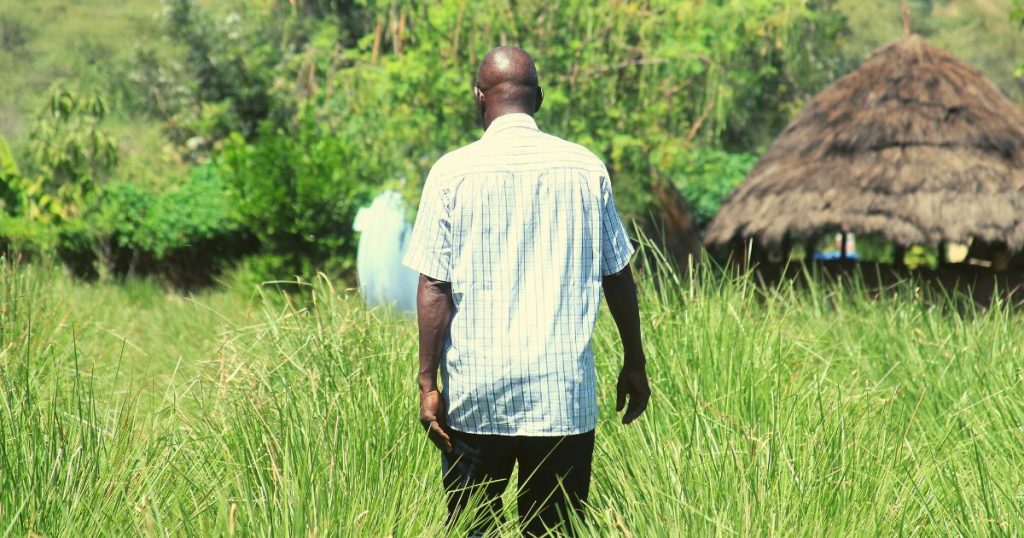

Teimuge, is a resident of Emsea village, found in the lower lands of Elgeyo Marakwet county. He is a pioneer of Vetiver grass farming in the area.

“Many of the surrounding lands are affected by gully erosion — deep gullies, some measuring 30 feet deep!” Teimuge says, motioning at his farm, as he walks on a small path, in between dense knee-high grasses, brushing through his trouser, as he moved about, noting that his land has one of the largest gullies, stretching a few kilometers away from his land.

A conversation between two friends was the beginning of Vetiver Grass growing project, in this area.

“A friend of mine who worked at Kenya Forestry Research Institute (KEFRI) introduced vetiver grass to me, saying that it is a non-invasive grass that would help combat Soil Erosion.” Teimuge says.

He has never looked back. Today, Teimuge farms Vetiver in an acre and a half piece of land.

According to Dr. Monica Nderitu, the Regional Environment and Climate Change Advisor at VI Agroforestry, vetiver is a perennial grass, which is used for soil and water conservation.

“This grass has deep root system that can extend to ten/ fifteen feet, making it useful on and off farmland, for water-sources stabilization and remediation of polluted soils.” Nderitu says. “Vetiver is highly effective in controlling soil runoff,” adding that, major rain events that follow drought season, is what causes gully erosion, hence it is advisable to plant vetiver on the slopes borders of the land.

Titus Kigen, a farmhand in charge of Teimuge’s farmland, says that they utilize sloping area to grow crops in between rows of vetiver and the rows of trees.

“We farm, without the need to spray pesticides.” Kigen says. “Pests are attracted to vetiver. They will lay eggs on the grass and forget about other crops in the farm.”

The nature of Vetiver grass, allows farmers to practice non-chemical management methods — this allows protection of Soil Biodiversity.

“Vetiver grass can not only be used as a biological pest control, but also, as a remediation for soil that has been polluted by agrochemicals.” Nderitu says. “It’s morphological characteristics, helps it to absorb and recover the degraded soil.”

Titus says they use Vetiver harvest for thatching, fodder for livestock and mulching, which improves soil moisture and fertility.

For Aaron Kangwony, a member of Konyasoi Vetiver network, grass farming is his main source of income.

“This project has become a family business – My wife and I propagate seedlings, which we sale to communities and generate enough earnings to pay school-fees for the children,” says Kangwony, who lives in Tilomwonin village, which sits about 2km away from the drying Lake Kamnarok, in Baringo County. “When I’m called to speak on training seminars, I carry with me seedlings to sale to the crowd.”

He states that neighbors too, come to buy fodder for their livestock, during the dry season. “We sell a sack of Vetiver for 200kshs per bag.”

Besides grass growing, these members of Konyasoi Vetiver Network, practice diversification of crops. Depending on the season, you will find; fruit trees, bananas, plantains, sorghum and cassava in their farms — planted using minimum tillage.

Teimuge provides training on all aspects of vetiver grass planting, land contouring, harvesting and plant preparation. He receives visitors to his farm for field benchmarking.

Joyce Wafula, a small- scale farmer in Elgeyo Marakwet, is a beneficiary of Teimuge’s training.

“When I first bought this land, the situation was discouraging, it was all bushy, nothing was growing here, in fact, when I asked the neighbors, which crop does well, I was told nothing grows here.” Joyce says.

When it rained, the water washed over the land, sweeping the soil away. She tried blocking the erosion with layers of stones, but the water would easily carry them too.

Eventually, Joyce decided to go online in search of a solution.

“I found Teimuge on the internet when I searched on google — How to conserve Soil,” Joyce says. “I contacted him, and here we are.”

Possibly the most impactful story of how internet connection can help elevate the knowledge incurred by Rural Women, comes from Joyce.

Today, Joyce farm produces varieties of crop yields, filled with different type of fruit trees and vegetables.

“I have learnt a lot about trees, I can easily identify a medicinal plant and extract oil or make soap out of them.” Joyce says.

“Sometimes back a friend called me, from a farmer’s forum. She told me that a book being handed over to the members in attendance had a picture of me in the front page,” Joyce narrated grinning from ear to ear. “It was a book that World Vision had written about me, touching on regenerative agricultural practice.”

The Konyasoi Vetiver Network members say they speak out, to inform others who may not have known the benefits of the grass, that this natural resource does help in minimizing the rapid erosion occurring in Kerio Valley — urging the community to adjust their socio-economic values in order to help combat Soil degradation.

Even though there are practical examples in Kerio Valley, showing that regenerative agricultural practice works in improving soil quality, the project hasn’t been adopted by many residences

According to the region County Commissioner, the issue lies with the community unwillingness to adapt to alternative economical ventures.

He stated that overreliance on large livestock as a social value and status in the community, is costing the lower-lands their land. The depletion of vegetation cover, leaves the land bare and vulnerable to degradation.

“I appeal to the community to practice Rational pastoralism. There is no value in keeping large livestock that get emaciated during dry season. Sale these livestock and put money in the bank and only keep small herd that are at per with the available forages in the region.” Korir says.

He further urged the community to take their children to school, noting that literacy will ensure a future where the society can survive without necessarily relying on large scale pastoralism, which is the major source of Cattle rustling menace in the region.

Rather than relying on age old practice, communities are urged to diversify and embrace drought tolerant crops— Millet, sorghum, plantain, cassava, beans, banana and mangoes are just an example of what is possible in the region.

“Exposed and vulnerable communities cannot afford to suffer the consequences of climate change, that is why embracing actions that build resilience is crucial, as it enables a community to adapt to a changing environment,” says Steve Itela, the Chief Executive Officer of Conservation Alliance of Kenya (CAK). “Don’t sit and wait for government support, because, that help comes a little, too late.”

“Faced with the climate change challenges, a community can either migrate, adapt or sit back and wait to perish.” Cheptot says.