Entrepreneurs and Innovators Take Center Stage at 2nd Agroecology Conference—Yet Policy Hurdles Remain

Nairobi — As the third day of the 2nd Agroecology Conference unfolds, light rain drizzles over the venue, dark clouds hanging low—a fitting backdrop as farmers and their allies gather at this four-day summit to discuss the future of their lands.

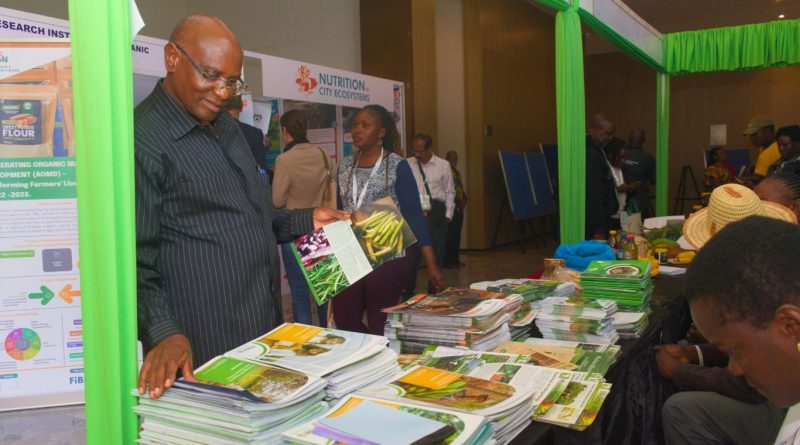

Across the conference grounds, exhibitors set up their booths, preparing for a day of engagement as attendees tour their spaces, observing innovations, exchanging ideas, and forging connections.

From innovative products to established agroecological practices, the event buzzes with energy. Each stakeholder hopes to leave with ideas that will drive meaningful change in the food system.

One of them is Nagudi Rita from Uganda.

Rita, an agroecology entrepreneur, is the founder of Pumzi Teas, a business that blends herbal teas using a mix of herbs, spices, fruits, and flowers—offering a natural alternative to traditional black tea.

“I started blending herbs at home just for myself,” Rita told Kass Media, recalling the personal story behind her venture. “I was looking for a natural way to manage my anxiety.”

At first, she made herbal tea only for herself, but when friends, colleagues, and neighbors sampled her blends, word spread. Soon, demand exceeded what she could produce by the kitchen countertop..

“The demand kept growing,” she said.

Rita’s teas are crafted using a natural, eco-friendly process designed to preserve their quality and potency. The herbs are harvested at peak freshness, cleaned, sorted, and then dried. Once dried, they are either left whole or ground into fine pieces.

However, early on, she faced a production bottleneck.

“Drying the ingredients in the open air took too long, and I couldn’t produce enough to meet orders. That’s when I started looking for ways to scale up using solar energy,” she explained.

Another young entrepreneur showcasing her products at the exhibition booth is Getrude Chambati, an agroecological entrepreneur from Zimbabwe and founder of Majestic Africa.

Her business has since expanded. She moved from drying herbs on her apartment balcony to setting up a standalone facility with solar dryers, increasing her production capacity significantly.

Another entrepreneur showcasing her products at the conference is Getrude Chambati, founder of Majestic Africa, a Zimbabwe-based agroecological enterprise.

Through value-added agro-processing, Chambati transforms indigenous crops—finger millet, pure millet, brown rice, local fruits, and herbal teas—into market-ready products.

In just five years, she has expanded from serving local customers to supplying corporate clients.

Her journey into entrepreneurship was fueled by two concerns: the loss of traditional dietary habits and the struggles of smallholder farmers in accessing markets.

“I wanted to help farmers see agriculture as a business,” she said. “By sourcing grains at fair prices and processing them naturally, my enterprise not only ensures healthier food options but also strengthens farmer-led food systems.”

Her work is part of a larger movement—across Africa, agroecological entrepreneurs are driving a shift toward more sustainable, farmer-centered food systems.

Chambati and Nagudi Rita are among 320 entrepreneurs supported by the African Agroecological Entrepreneurship (AAE) project, an initiative of the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA).

“Through this project, small-scale food producers are finding pathways to scale their impact while staying true to agroecological principles,” said Ruth Nabaggala, AAE project officer at AFSA. “The work of these entrepreneurs offers a glimpse of the project’s broader impact.”

Nabaggala said that the AAE project, currently active in Uganda, Zimbabwe, Ghana, and Tunisia, is equipping entrepreneurs with the skills, networks, and market access they need to scale their businesses.

“Many of these entrepreneurs are innovating in organic fertilizers, indigenous seed preservation, and sustainable food production—key areas that support climate resilience and strengthen local economies,” she said.

However, despite their dedication, many agroecology entrepreneurs still face significant barriers, including limited access to financing and policy support.

“In some cases, banks require a minimum of five acres of land before considering loan applications, locking out small-scale farmers,” Nabaggala said. “The project is also working to strengthen local markets and champion for supportive policies to help these businesses thrive.”

She said that agroecology entrepreneurship is more than a business for profit—it’s a commitment to healthier communities.

“It creates sustainable livelihoods, preserves indigenous knowledge, and strengthens communities,” she said. “It goes beyond profit, focusing on human rights, environmental well-being, fair trade, and shorter supply chains that benefit both farmers and consumers.”

“Beyond restrictive financial policies and lack of institutional support, national agricultural policies still favor industrial farming over sustainable practices,” Nabaggala said.

One of the key concerns raised at the conference, echoing Nabaggala’s sentiments, was the widespread use of chemical pesticides in Kenya. These pesticides not only degrade soil health but also pose serious food safety risks.

Dr. Monica Nderitu, Regional Environment and Climate Change Advisor at Vi Agroforestry. Speaking at a session on promoting safer alternatives in agriculture, she illustrated how advances in agroecology are helping farmers adopt innovative, climate-smart solutions that boost productivity while preserving soil health.

She stressed the need to reduce reliance on synthetic pesticides through alternative methods such as push-and-pull pest control, indigenous pest management techniques, and biological pest control.

“This shift improves soil health, conserves biodiversity, and boosts farm productivity,” Dr. Nderitu said.

Dr. Nderitu’s concerns are not just theoretical—they reflect a growing crisis in Kenya’s agricultural sector.

Recent reports have revealed alarming levels of harmful pesticide residues in food, affecting both local markets and exports.

In response to these findings, organizations such as Route to Food and the Kenya Organic Agriculture Network (KOAN) are pushing for stricter pesticide regulations.

“Many of these pesticides contaminate soil and water, making it harder for farmers to transition to organic or sustainable agriculture,” said Eustace Kiarii, CEO of KOAN. “If we don’t act now, we risk not only public health but also the fertility of our farmlands.”

His warning adds to the growing debate over pesticide regulation and the urgent need for safer alternatives.

Phasing out harmful pesticides in the country is unlikely to succeed—or gain support from the pharmaceutical industry—without strong backing from the government. Civil society leaders are calling for lobbying efforts aimed at Members of Parliament to pass supportive laws.

Deputy Speaker and Member of Parliament Gladys Boss Shollei criticized the Pest Control Products Board (PCPB) for failing to act, despite overwhelming research and international bans on these chemicals.

“You don’t need further research. These harmful pesticides are already banned in Europe and North America—yet they remain legal in Kenya,” Shollei said. “The Pest Control Products Board has failed this country. I will continue pushing for their removal from office.”

In Kenya, pesticide bans follow strict regulatory procedures under the Pest Control Products Act (Cap 346), overseen by the PCPB.

However, decisions on pesticide bans or recalls involve multiple agencies, including parliamentary committees, which sometimes push for policy reviews.

Shollei said that similar swift regulatory actions had been taken in Kenya before—such as banning certain cough syrups and hormonal therapies due to health risks—questioning why pesticides with proven links to cancer were still permitted.

Dr. Nderitu called for greater investment in research, financial incentives for bio-input producers, and stronger regulations on harmful pesticides to create a more sustainable and farmer-driven agroecological transition.

“The evidence is clear—synthetic pesticides are harmful. Now, the focus must shift to empowering farmers with access to safer, sustainable alternatives through research, investment, and policy reform,” Dr. Nderitu said.

As policymakers and researchers debate stricter pesticide regulations, some small-scale farmers are already testing organic alternatives.

One such approach is being pioneered in Uganda.

Irene Nakijoba, a farmer from Mukono District and a member of Eastern and Southern Africa Small Scale Farmers Forum (ESAFF) Uganda, shared her group’s innovative approach—using fermented human urine as both a fertilizer and pesticide.

Through hands-on trials at their demonstration farm, Nakijoba and her group have tested this organic alternative, proving its effectiveness.

“At first, many people doubted whether human urine was safe to use, especially on food crops like vegetables, maize, and bananas,” Nakijoba said. “But after we demonstrated its effectiveness through our trials and shared our visual documentation, people were convinced and took this as a learning experience.”

She and her team set out to provide practical, evidence-based solutions—an approach that is both sustainable and cost-effective.

Nakijoba said that they collect urine from households, including from children and the elderly, ensuring that proper sanitation measures are taken.

The collected urine is stored in sealed containers in a shaded area for 14 to 21 days. During fermentation, harmful pathogens are neutralized, and ammonia and methane levels drop, making it safe for crops.

“Once fermented, the urine is highly concentrated and must be diluted before application,” she said. “For vegetables, for instance, we mix one liter of urine with eight liters of water. We also add ash to enhance its effectiveness. To convert it into a pesticide, we mix in herbal additives that act as natural repellents against insects that attack crops at night.”

Irene said that when used as a fertilizer, the urine is applied around the roots of the plants to deliver essential nutrients. As a pesticide, it is effective at repelling insects, particularly those that attack crops at night.

Nakijoba and her fellow farmers are scaling up their work, encouraging more farmers to expand the use of bio-based alternatives that support sustainable agriculture.

“Agroecology isn’t new to us—our ancestors farmed this way, working with the land. But with today’s challenges, it feels like our only hope,” Nakijoba said.

As the third day of the 2nd Eastern Africa Agroecology Conference concluded, stakeholders reflected on key takeaways ahead of the final day’s field visits—where agroecology moves from theory to practice.

A mix of reactions filled the hallways as delegates slowly packed their belongings.

Attendees expressed optimism about the growing focus on agroecology, particularly the inclusion of small-scale farmers in discussions; ‘which I think is a recognition of the value we bring to our land and climate,’ Nakijoba said.

“There’s no stopping an alliance with a mission,” said Dr. Million Belay, General Coordinator of AFSA.

“AFSA is a movement of movements, working to transition African agriculture towards agroecology. That is why we brought our members here—to showcase what can be achieved through agroecology.” Dr. Belay said.

While he acknowledged that important discussions took place, Belay stressed that the fight for agroecology as a movement is far from over.

“To counter the dominance of industrial agriculture, we need to mobilize knowledge, build grassroots networks, and push for systemic change. Our food system is controlled by a few powerful actors, and we must amplify the voices of our farmers,” he said.

Belay said that, “agroecology is more than a farming practice—it is a movement for resilience, climate adaptation, and food sovereignty.”

Already looking ahead to the 3rd Agroecology Conference, with Uganda as a potential host, he stressed the need to deepen the movement-building aspect of agroecology.

“We must go beyond discussions and ensure that agroecology is not just seen as a farming practice, but as a force for resilience. Yes, we have made progress in addressing key issues like gender, youth, and trade, but we must ensure that agroecology is recognized as a powerful social and political movement.

Dr. Belay acknowledged that while farmers have long participated in trade, the challenge now is ensuring consumers can access food grown through agroecological practices.

“There is a gap in harvesting, packaging, branding, marketing, and selling—steps that are often overlooked in the value chain,” he explained. “If we want consumers to access healthy, sustainable food, we must strengthen the entire agroecology system, not just production.”

He said that youth and women should be at the center of this transformation.

“Young people and women are key to building a thriving agroecology economy,” he said. “They must be mobilized across the value chain—from harvesting to branding, marketing, and selling—to ensure that sustainable food reaches consumers. There are many opportunities in agroecological entrepreneurship, and we must create an enabling environment for them to participate.”

As the day winds down, the conference hall hums with traditional songs, laughter, and lively chatter. Though an expedition awaits tomorrow, this marks the official close of the conference.

At the exhibition booth, Rita carefully packed up her products, reflecting on the stakes at hand as the conference drew to a close.

“Without the necessary interventions to support agroecology, we risk losing the traditional farming practices and local knowledge that have shaped our culture and landscapes for generations,” she cautioned. “And with that loss, we also jeopardize the availability of truly healthy, sustainably grown food—the kind that nourishes both people and the planet.”